Tiretti Bazaar by Bijoy Chowdhury

- Vidura Bahadur

- Nov 1, 2021

- 6 min read

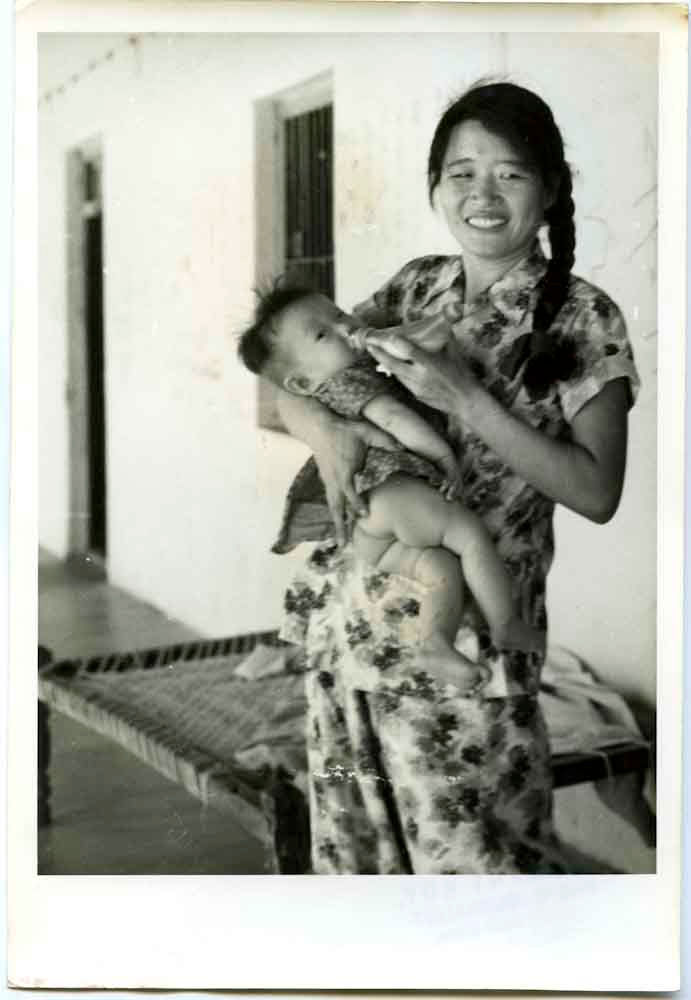

Explore Tirretti Bazaar through photographer Bijoy Chowdhury's intimate portraits of the Indian Chinese community settled in and around the the bazaar.

A voice floats through the cell phone I hold close to my ears – “Bijoy, what’s going on? When will all this trouble end? This does not seem right.” The voice does not pause to breathe. There is a clear anxiety in that voice. And, the voice belongs to my Chinese-Indian friend from Kolkata, Asi Hong. Hong and I have known each other for a long time. He owns a small shoe shop at Bentinck Street in Kolkata. Right before the lockdown was declared, I had sat in that shop, for long adda sessions with Hong and my other Chinese friends.

Asi Hong’s shop has remained closed ever since the lockdown. Hong keeps watching the news of the Indo-China skirmish in Ladakh. “Boycott China,” the political leaders shout from the other end of the screen. I could sense his fear and anxiety. I try to provide assurance tomy friend as best as I can.

Hong’s anxiety cannot be dismissed off as “baseless.” After all, during the Indo-China War in 1962, many from Kolkata’s Indo-Chinese community were sent to detention camps in Rajasthan. That memory of humiliation remains within the community, like a festering wound. That’s precisely why the news of the bloody skirmish with China in far-off Ladakh sent ripples of anxiety and fear through the Chinese communities in the alleys of Tangra and Tirrity-Bazaar in Kolkata.

The ancestors of the Chinese communities who live in these neighbourhoods, came to the city through the Achipur region in Budge-Budge, about two hundred and fifty years ago. That’s what the historians tell us.

To be honest, no one in the community should have to harbour this anxiety. All of my Chinese friends have all the necessary documents – birth certificates, Aadhar, Pan Card, Voter Ids, Indian passport. Like you and me, they stand in queues to vote. Pay their taxes. But simply because their faces bear the markers of a “Mongoloid” identity, they have to suffer from a certain kind of anxiety. They are often treated as “others.”

It would not be untimely to remember in this context, how a nurse from the Northeast was treated recently in Kolkata by the passers-by. Because of the same reason -- her face bears the marks of a “Mongoloid” identity. She was shouted at, and was called “chinkie.” Apparently because the COVID-19 virus originated in China. Can we still call ourselves “civilized”? Even some of my Bengali friends had warned me – “Bijoy, please be aware of your Chinese friends during this time. Be careful. Don’t go to their localities and eat their food. Take care.” More than a concern for my well being their voice had a hint of disapproval for maintaining friendship with people from the Chinese community.

For the last twenty years, I have been working among the Chinese community in Kolkata. It started In 2000, when a Mumbai-based magazine hired me to do a photo-story on the community. A journalist from Mumbai came, and with her, I explored the deep alleys of the Tangra and the Territy-Bazar area. Chinese newspapers, Chinese schools, Chinese Kali Mandir, eating houses, the Chinese breakfast market that opens at wee hours of the morning, Chinese clubs – a different Kolkata unravelled itself before my eyes. It was a wonderful time.

My photographs were published, I was paid for the assignment. After a few days, for reasons I can’t really explain, I began to explore the same neighbourhoods on my own. I began to have Chinese friends. My Chinese friends began to invite me to shoot the births, deaths, weddings, New Year celebrations in their community. I would also often join my Chinese friends for drinks. The discussions in such addas were not always very polite, proper or “ politically correct.” Slowly, we began to form extremely close bonds with each other. The addas at tea shops at Tirrity Bazar, were just like any other para addas. Opinions were expressed about Sachin, Sourav, Dhoni and Viraat. Heated debates took place. Deep analyses of the songs of Rafi and Mukesh were done, fights were fought over who is better. Laughter, pulling of each others’ legs and fun constitute the predominant mood of such addas – just like any other tea-shop adda in Bengal. The cleanliness and devotion with which the pujas were conducted at the Chinese Kali Mandir, would probably put us to shame. When we line up for Chinese breakfast at Tirrity Bazar, my Chinese friends line up for aloo kachuris, which, at Tirrity Bazar, are often known as “kamalapuri.” Chinese celebrations served biryani and chaap.

A few days ago, I ran into my friend, Mr. Samson. Mr. Samson, a Chinese-Indian man, is moving up in years. He had just returned from a visit to his son in Canada, who had moved in there for good. I joked with him – “Mr. Samson, why are you back so early? Could have spent a few more days.” Mr. Samson shoots back – “No, no, Mr. Choudhury. Never— I have been to many places. But East or West, Kolkata is the best. In foreign lands, there is plenty of money or affluence. But unlike Kolkata, there is no heart. No one will speak to you for a minute. Everyone is so busy. Everyone is running after money. Even my son and his wife do not have much time for me. That’s why I am back in Kolkata. And this is where I want to live till I die.”

About three years ago, a photography exhibition on Santiniketan and his Cheena Bhavana, was organized by the University of Peking at Beijing.I was there. When I came back, my Chinese friends asked me lots of questions about their ancestral land – about food, the streets, human beings, Chinese Wall. They kept asking questions repeatedly and incessantly. I felt a kind of guilt. They should have had the chance to visit their ancestral land. On the other hand, I had been there, and not only that, I am the one who is telling them stories about it.

My story would remain incomplete without Miss Stella Chen. She was around 62 years, and owned a store called Hap Hing Co. at Sun Yat Sen Street. Slightly chubby, heavy-set and with glasses, Miss Chen was extremely fair-skinned. Her father had established the shop that she inherited. She sold green tea, rice noodles, different kinds of herbs and herbal products, and medicines. A visit to the shop would take you back by at least 100 years. Inside the shop, there were black-and-white photographs of her father and her grandfather. The line-drawings, the abacus that her father had used, and wooden chairs from her father’s time, had also been preserved with great care.

Often in the mornings, I would go and chat with Miss Stella, primarily because of the easy affection she offered me. Stella, in the middle of providing her customers with whatever they needed, would also keep talking about the Chinatown of her childhood. Both the joys and the sorrows. She was a good storyteller and could describe things in great details. I would always be the amazed listener. “Bijoy, do you know, this building used to house thirty to forty Chinese families. Now, only three or four are left. Everyone else has left.” Even Stella’s siblings have settled in the USA. Stella would continue, “ You know, Bijoy – they are asking me to sell the shop and the house and to live with them. But, how can I sell my father’s memories, tell me? Besides, this is the city where my friends and neighbours live. Here, I roam around freely, talk freely, chat with others freely. As I wish. What more can I want from life?”

“Have your brothers stopped visiting?” I asked.

‘Yeah, they will probably come when I am dead.” Stella threw a vacant gaze, and there was a hint of what we call abhiman in Bangla.

About six months later, I got a phone call from one of my Chinese friends – Ah Kong -- at around 11 a.m. I was in the bazaar at that time.

“Bijoy, you know, Stella Chen has expired. You need to come quickly.”

I was stunned to get the news. Somehow, I dropped the groceries at home, and rushed to Chinatown. Stella was in the habit of waking up very early in the morning. On that day, when they didn’t see her, the neighbours began to call her. On not hearing anything, they broke open the door, and found Stella lying on the bathroom floor, with blood around her. She had died from too much bleeding.

The doctor came. Stella’s body was kept in the cold room in an ice freezer. Her siblings in American were informed. After a couple of days, they let us know that they won’t be able to come to attend her funeral. Her neighbours took her to the Tollygunge burning ghat. I, too, followed them. When Stella was burning inside the electric oven, I was thinking, it’s not just Stella’s body that is burning. Also burning along with her are years of carefully preserved histories of memories. A few friends and myself, collected her ashes and came to the river at Babughat.

I have been to Babughat before, to shoot the immersion of goddess Durga. Now, it’s a very very loved one – Stella – whose immersion I was watching. What kinds of jokes destiny can play on you! The earthen pot carrying Stella’s ashes kept floating in the holy waters, and finally it drowned – in search of eternal peace.

For more details about the photographs please contact bijoychow@yahoo.co.in