Ah Leen's Story - Part 1

- Jennifer Liang

- Sep 18, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 7, 2020

Ah Leen’s Story Part 1

My father comes to India

My name is Ah Leen and I was born in Sui Thang village of Canton in China.

An adventurous soul, my father’s father had gone all the way to dig for gold in America. He did not bring back much gold - for he remained largely poor – but he brought back to China certain habits. Like walking around the village in a Western suit and hat, carrying a walking stick. The villagers called him kam saan lao (gold mountain man). His wife died very young but he refused to marry again, fearing ill-treatment of his sons in the hands of a step-mother. He thus brought them up single-handed.

It was tough times in China in the 1920’s. Famines, warlords, Nationalists fighting the Communists ….Work was scarce and food becoming scarcer. Many men moved out of China to search for work and make a living. My grandfather, the Gold Mountain Man decided to send his elder son called Ah Ping (who he thought smarter and more industrious) to India, a land of milk and honey with rich prospects. Many from their fellow villagers were already there. They had work, could make a living and even managed to send money home to help out.

My father, like many others in his district of Soon Tak near the sea, was a carpenter. He made wooden dinghys for a living. With no money in his pocket but carpentry skills in his hands, my father landed in India in 1925.

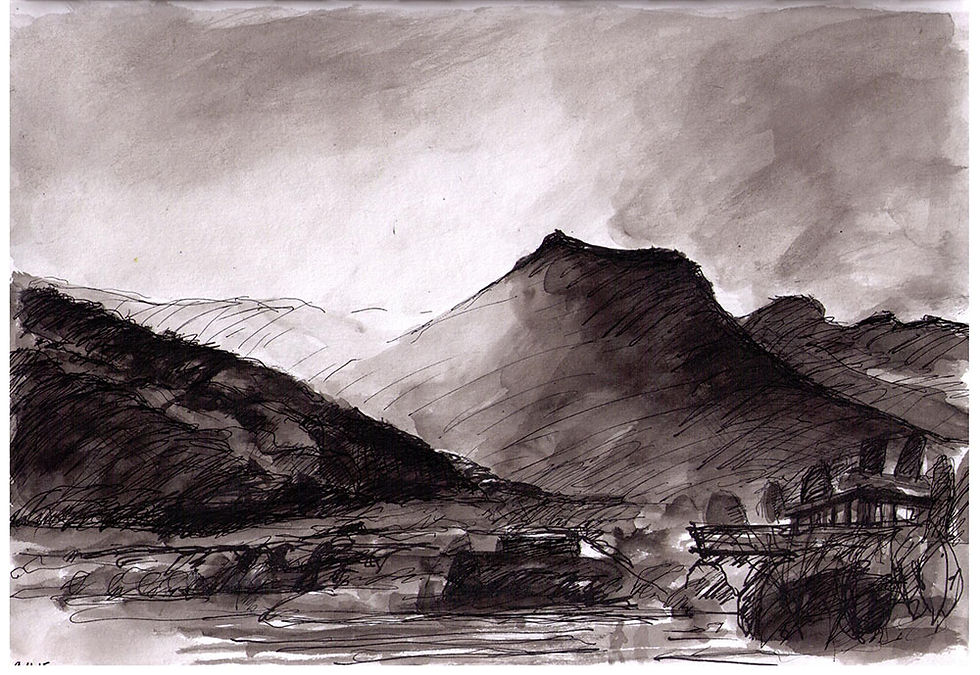

Tea gardens in Assam and North Bengal already had many Chinese carpenters but seemed to need even more. Carpentry skills were needed to build houses, factories, racks and even wooden tea boxes. Most tea gardens In Bengal & Assam hired Chinese carpenters from our region district to work. Soon after docking in Calcutta, my father made his way up to the tea gardens near Siliguri, in the shadows of the Himalaya mountains He worked under different master carpenters in various tea gardens of Assam and Jalpaiguri.

For 5 years, he worked and honed his skills.

He was then introduced to a girl – Ah Ngan - whose father was also a Chinese carpenter from a village not far from my father’s village in China. He thus married her and after some time, set off to China with his bride. My mother was six months pregnant then.

Parents Go to China

He was going home with a princely sum of 2000 rupees in his pocket, a wife and a child-to-be-born. They could even afford tickets in a passenger ship for the month-long journey. In their excitement on landing back in China, both my parents fell into the water while getting off the ship. My mother who could not swim hung on tight to my father’s legs, determined to die together if they had to. Luckily, they were rescued or else my story would not have been born.

With the 2000 rupees they brought back, my parents lived quite comfortably in China for three years. My sister was born and then I followed in 1933.

But things got worse in China – the Emperor was overthrown and the Japanese took control of North China and soon, they were marching to our region. There was chaos and once again, my father could not find work. With more members now to feed, he needed money. He again left for India leaving my mother, my sister and me back in China with the Gold Mountain Man, my grandfather.

My mother kept pigs and hens and farmed vegetables under the tutelage of my grandfather.

Then, when my mother’s father came to China to find a bride for his only son, the Gold-Mountain Man decided to send my mother back to India with him. He wanted my mother to join his son in India and produce him some grandsons. My grandfather kept back my elder sister in China as she had to start school and he also feared my parents might not come back if they had both their daughters with them. My sister was 6 years old then and we never ever saw her again. The Japanese captured our province and many children in China then starved to death or were sold by desperate, starving families. My sister might have been one of those children.

I Reach India

This time my mother had lesser money in her pockets and so we travelled less comfortably in a goods ship called Chou Saang. The tickets costed sixty rupees a person and we had four other Chinese families with children who were our shipmates in our journey to India, We developed a special bond between us and years later, my mother remained close to our shipmates. Even after we grew up, we children kept in close touch. The ship went via Penang, Burma and other places. After a month, we reached India.

It was 1935. I was in India. I was 2 ½ years old and 2½ feet tall.

We joined my father in Jalpaiguri but he did not have a permanent job. We stayed in different tea gardens where he would do small carpentry jobs. In the year 1937, my first brother was born and our luck also changed.

My father got a permanent job as a carpenter in a tea garden owned by a British company. It was a good job – well-paying and we were given living quarters and two servants to help us. My second brother was born there. Out of his 60 rupees monthly salary, my father would first send 10 rupees to his father in China and save 10 rupees in the post office (he wanted to send my brothers to Calcutta to study English when they grew up).

Every evening, our nanny would take us to play with the children of the chota sahib (the No.2 boss in the tea garden) – an Englishman married to an Indian lady. We were happy but our happiness was short-lived. We were just celebrating my father getting a permanent job when he contacted fever and in three days’ time, he was dead. I was seven and my younger brothers were three years old and 10 months old.

The Englishman tea garden manager was very good to us. He allowed us to stay an extra month in the house and then gave us a small truck to carry away our household goods. We left the tea garden.

My mother had to find a way to feed us. Her mother – my boju - stepped in to help.

Mother’s Mother – My Boju

My mother’s mother was a Nepali from a high caste Brahmin family in Bhutan. They were herders who kept cows and sold milk for a living. She and three of her friends came down from the mountains to meet some relatives and roam around the plains. All four young girls ended up marrying Chinese carpenters and out of shame and shyness, they never went back!

My grandmother called Bishnu Maya lost all contact with her parents and siblings. Many years passed. One day she was travelling in a jeep with one of her children on her lap. The jeep suddenly passed another jeep and she spotted her brother in it. He also saw her. They stopped the jeep and in the middle of the road, the brother-sister clung on to each other and cried and cried – just like lost-and-found siblings in Hindi movies. From then on, my uncle used to come down from the mountains once a year after dasai (the Nepali New Year), bringing milk sweets made from thickened cow milk.

It was this same Bishnu Maya who came to the rescue of her daughter – my newly widowed mother and us, her three children. She gave us a small house to live in and helped us rent a small plot of land near Hamilton Bazaar and we started our new life.

Life in Hamilton Bazaar

My mother’s skills at growing Chinese green leafy vegetables picked up in China in her 6 years there, came to our rescue. She has been well-tutored in farming by her father-in-law in China (the Gold Mountain Man, who incidentally died of a heart-attack when he read the letter of my father i.e. his son's death in India). Anyway, here in Hamilton, we paid twelve rupees a year as rent for the 6 acres of land on which my mother planted different types of choy or green leafy vegetables. We would sell these to the Chinese carpenter Ah Paks (uncles) who worked and lived in the different tea gardens around Hamilton Bazaar and would come to the market every Sunday.

At the age of 7, I had to cook. Since my mother had to work in the fields tending the vegetables, she would tie my baby brother with a cloth on my back and I had to cook lunch and look after my two brothers. I lost count of the number of times I would accidently burn myself while cooking. My mother's sister would sometimes come and help me with my cooking. We were only two Chinese families living among 40 Nepali families. All my friends were Nepalis. We not only spoke Nepali most of the time but would also eat Nepali and Indian food. It was simpler and cheaper. Chinese food was more elaborate as one needed to cook soups, meats, vegetables. Hence, we would eat Chinese food in the house as a treat.

Every Sunday, the Ah Paks would come to the weekly Hamilton Bazar– to shop, to eat, to drink, to gamble, meet friends and catch up with the gossip of near and far. Bazaar day was the most important day of the week for us. For a small payment, my mother and I would also cook for the Ah Paks, mend their clothes and knit them sweaters. My two brothers would mind their bicycles for them and run errands for them – like getting them a pack of cigarettes or getting them snacks from the shop. They would pay us some small coins for these errands.

We also kept hens, goats and even pigs for extra income. Once, my mother and I bought a pair of piglets for seven rupees. Rearing them was hard work. I would walk for miles into the jungle … collect wild roots and vegetables, then clean and cook them for the pigs. But they grew nice and fat. Our happiness knew no bounds when one of the Ah Paks ordered both the pigs for his son’s naming and head shaving ceremony when the child would complete a month. He promised us 70 rupees for both the pigs which he would come and collect the following Wednesday. My mother and I already started dreaming of all that we would do with the money the Ah Pak would pay us. We woke up on Tuesday morning and found the bigger of the pigs, dead. It lay on its back with all four feet sticking up to the sky. Mother and daughter – how much we cried at our misfortune! But the Ah Pak was good. He took the smaller pig but still paid us half the promised price.

We never reared pigs after that. But we had a lot of chickens and ducks….And if the fox did not get them first, we could sell them for a good price.

Ping Kai & the gang

We were four Chinese children there in Hamilton and were something of a gang. Our ring-leader was the fourth Chinese called Ping Kai who like most of us, was also born in the tea garden. We had busy days. Ping Kai would take us to station wagons parked in Hamilton Station and we would steal some coal from there for our stoves at home. When our cloth football tore, he would teach us to play football with a skull he would get from the nearby cremation ground. One day we dribbled the skull and left it at the door of the village Pradhan (head man). His wife almost died of fright. Ping Kai was also superb with his slingshot. He would collect bets from all of us for breaking matkas (mud pots) from afar as women balanced two or three of the water-filled pots on their heads while going home from the river. With his catapult, Ping Kai could aim and break exactly the pot we pointed out to.

There were no schools nearby and so my mother requested a Bengali man to teach us Chinese kids in his home along with his own sons and a few other children. We would sit in the floor of his veranda and he would teach us the Bengali alphabet.

One day Ping Kai found a whole lot of tablets thrown next to a medicine shop. He collected them and distributed it among all the children in the school. The master’s son got the biggest share to eat. We all ate it and went home after school. How we all slept and slept. Some of the children didn’t wake up for over 24 hours! It’s a wonder no one died. The master was so angry that he threw all of us Chinese out from his classes. That was the end of our studies there. I never attended a proper school. My uncle who could not read or write would pay 25 paise to send me for a few hours of tuitions a month to learn some Hindi. Six months later, he demanded 'repayment' for his investment in my studies. He wanted me to write a letter to his son working as a carpenter in Assam. I had only learnt a few letters of the Hindi alphabet by then. But even later, I would copy the same few sentences in every letter to his son in Assam month after month!

But Ping Kai was famous. He was much in demand to play for the football teams of the different tea gardens. As the only Chinese boy in the team, he was quite recognizable and well-known. Much later in the 1962 border war between India and China, Ping Kai’s family was arrested and taken to the Rajasthan camp along with many other Chinese families, including my uncle and other relatives. He was then sent to China along with his parents and siblings. Many years later, we learnt that they had a very tough life out there in China but Ping Kai, with his football skills became a football player there and later a football coach.

Leaving Hamilton

It was 1948. India had just gotten Independence a year ago. We got a letter from my uncle (my father’s first cousin) who lived in Calcutta. Fearing my brothers would not have any schooling and remain illiterate if we lived on in the bondooks, he invited my mother and the three of us to move to Calcutta and live there. The larger fear my uncle had was that if we lived on in the village, we would lose every bit of our Chinese culture as already, our food was Nepali and though we could understand Chinese, we spoke it haltingly. My uncle’s mentor and godfather had just died in Calcutta leaving behind a soda shop and since he himself had a job as a carpenter in the government owned telephone company, he could not run the shop himself and needed help.

My mother and all our relatives decided that for the future of us children, we should move to Calcutta.

My mother’s brother who used to work as a carpenter in the new airport that was being built in Hashimara, decided to treat us. A small cargo plane carrying tea went a couple of times a week to Calcutta. Only 4-5 passengers were allowed in it. He bought tickets at Rs.60 each for the four of us. The excitement of flying for the first time helped distract us from the huge sadness we felt in leaving behind the only life we knew. But it was also very festive. All relatives and indeed the entire village of Hamilton Bazaar took the chance to come to Hashimara to see us off at the airport – and also see an aero-plane for the first time. If only the Chinese school in Maal Bazaar (three hours away by train) started before we left, my brothers might have gone to school there and we would not have come to Calcutta at all. My mother had a thousand rupees saved from years of toiling in the vegetable garden and I had three hundred rupees from all the hens and pigs we had reared and sold. We left the Hamilton Bazaar in the Himalaya foothills for Calcutta to begin the next phase of our lives.

To continue reading please click here for Part 2, click here for part 3